Voices Of Freedom

Exhibition

on the occasion of remix ID Vienna

Artists Renee Renard and Remix ID

Artistic Director Olga Torok

Curator Mirela Stoeac-Vladuti

Co-Curator Denise Parizek

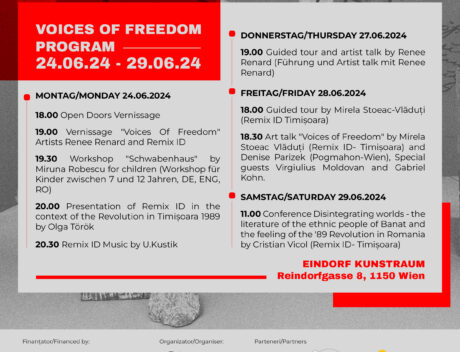

PROGRAM

Montag/Monday 24.06.2024

19.00 Opening: „Voices Of Freedom“ Artists Renee Renard and Remix ID

19.30 Workshop „Schwaben haus“ by Miruna Robescu for children (für Kinder zwischen 7 und 12 Jahren, DE, ENG, RO)

20.00 Presentation of Remix ID in the context of the Revolution in Timișoara 1989 by Olga Török

20.30 Remix ID Music by U.Kustik

Donnerstag/Thursday 27.06.2024

19.00 Guided tour and artist talk by Renee Renard

Freitag/Friday 28.06.2024

18.00 Guided tour by Mirela Stoeac-Vlăduți (Remix ID Timișoara)

18.30 Art – talk „Voices of Freedom“ by Mirela Stoeac Vlăduți (Remix ID- Timișoara) and Denise Parizek (Pogmahon-Wien).

Samstag/Saturday 29.06.2024

11.00 Conference Disintegrating worlds – the literature of the ethnic people of Banat and the feeling of the ’89 Revolution in Romania by Cristian Vicol (Remix ID- Timișoara)

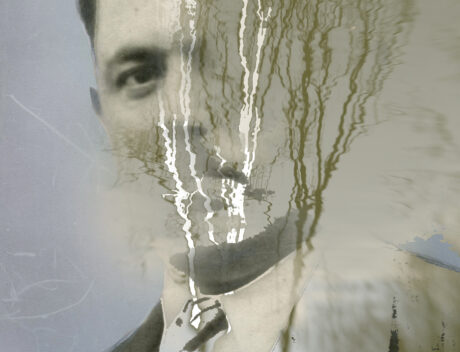

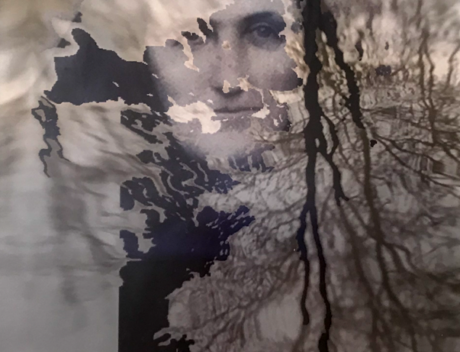

Image credits: Mute Insurgent & Renee Renard

Voices Of Freedom

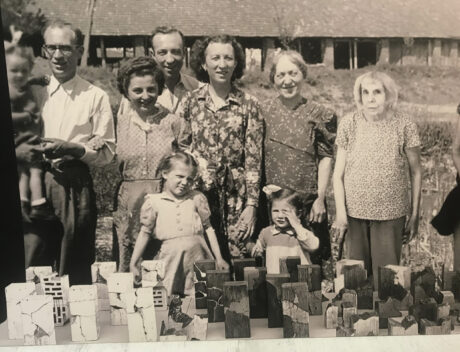

REMIX ID – VOICES OF FREEDOM brings the stories of the minorities from the Banat region during 7 days of exhibitions, workshops, presentations, and conferences.

REMIX ID, a project created by META Spațiu Association, is one of the most valuable Romanian initiatives to recover the traditions and history of the ethnic communities of Banat.

This project is co-financed by the Romanian Cultural Institute, through the Cantemir Programme – a funding programme for cultural projects for the international environment.

Therefore, from 24-30 June 2024, the life stories, influence and ethnic heritage of the ethnic communities of the Banat region and Timișoara, which have decisively influenced the mentality and collective identity of Romania, especially in the western part of the country, will be the subject of an exhibition by the artist Renée Renard in Vienna, at Eindorf Kunstraum gallery.

During the period in which the exhibition, accompanied by a Remix ID video installation, will be on view, the Viennese public is invited to participate to workshops, presentations, concerts and conferences on the impact that multiculturalism in the region has had and is having on the present and future of Timișoara and the Western region, held by Mirela Stoeac-Vladuti, Olga Török, Cristian Vicol, Renée Renard, Denise Parizek, Miruna Robescu and others.

REMIX ID – VOICES OF FREEDOM explores how minorities in Banat, along with a nostalgia for the Central European past and the often traumatic ethnic emigration of the 1970s and 1980s, contributed to a dissident sentiment among the inhabitants of Timisoara. This sentiment was one of the driving forces behind the anti-communist revolution that began in Timisoara on 15 December 1989.

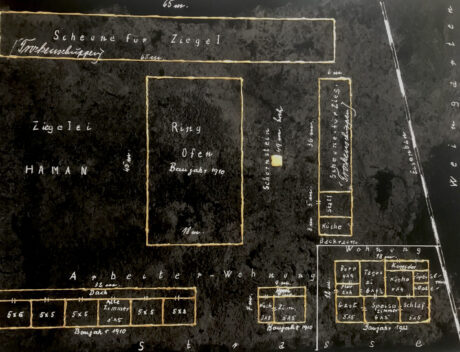

Remix ID is a Romanian cultural project of the META Spațiu Association, whose aim is to recover, through collaborations with music producers, composers, visual artists and writers, the traditions, music, customs, and history of the ethnic groups of Banat, one of the most diverse and multicultural areas of Europe. Started in 2018, the Remix ID project thus aims to create a dialogue between the vibrancy of the village and the frenzy of the city. Created together with artists who have been documenting the cultural typologies of rural and urban environments for 6 years, its activities superimpose the technologized world over the archetypal countryside life of today and the past.

In 2019, Remix ID received a mention from the Austrian Ministry for European and International Relations in the „Intercultural Achievement Award“ for bridging „past and present using art and technology by reproducing the stories of the ethnic groups of Banat – a place of diversity, intercultural exchange and cohabitation. The documentation and interviews they have taken with representatives of the various historical ethnicities facilitate access to these traditions for those interested, especially for young people, by remixing music and transforming traditional symbols and objects into contemporary art.“

___

ROMANIANS AND AUSTRIANS

text by Denise Parizek

The Austrian glorification of the Habsburg era rarely refers to the diversity of the multi-ethnic state and the oppression of minorities.

The monarchy was a multi-ethnic state, so Austrian culture lies in the diversity of the population. Several nationalities settled, mainly Germans, Magyars, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians, Romanians, Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Italians.

The population developed through a mixture of different cultures, be it in the culinary sector, in art and literature or in social interaction. Around 1910, the group of German speakers in the monarchy was slightly more than 20%.

If Austria is looking for something like a guiding culture, then it is the diversity that characterises the country. Same for Romania.

In 1910, there were around 3.5 million people living in the Kingdom of Hungary who professed to belong to the Romanian language group, which corresponded to 16.1% of the population of the Hungarian half of the empire.

During the Ceaușescu era, the West, including Austria, was more fixated on the idea of Romania as a bastion against communism than looking behind the scenes.

It was only in the 1980s that reports from dissidents unsettled the Austrian attitude.

But more and more refugees changed the political mood until the asylum law was changed. Politicians and the general public saw the entry of Romanians, which had increased particularly since the opening of the „Iron Curtain“ at the Austro-Hungarian border in May 1989, as evidence of this fear.

The background for the significant tightening of asylum laws by the Austrian federal government, a grand coalition between the SPÖ and ÖVP under Chancellor Franz Vranitzky (SPÖ), was the debate at the time about Romanian refugees and asylum seekers. The disputes in the media and politics, which were characterized by racist and xenophobic resentment, dominated the discourse and inflamed public opinion. This changed the legal framework for dealing with refugees and migration for decades to come and laid the foundation for the country’s asylum policy in the early 1990s.

The refugee movement from Romania then became a major media and political focus at the end of 1989, when the news and images of the nationwide protests and the fall of the Ceauşescu regime were widely publicised in Austria. A wave of solidarity arose and was reflected in an increased willingness to donate to the population in Romania. Aid transports with food, medical products and hygiene articles were carried out by organizations such as Caritas, Volkshilfe and the Red Cross. The focus remained on „local aid“.

In contrast to the citizens of the GDR, who attempted to flee via Hungary and had all the support and sympathy of the population in Austria, the assessment of the Romanian refugees who used the emigration flow of GDR citizens was completely different.

There were obscene statements from leading politicians:

Austrian Foreign Minister Alois Mock (ÖVP) remarked at a meeting of the Council of Europe in March 1990. „In politics, you simply need the consent of the Austrians. And the Austrians have been very generous for decades,“ emphasized Mock, referring to earlier refugee movements. „But now this practice must end, because we are not responsible for the fact that a communist regime ruled there for 40 years and left behind a terrible legacy,“ said the Minister.

The assumption of the politicians was that the GDR citizens would certainly soon be traveling on to their homeland, Germany, while the Romanians would stay in Austria.

A little fact in passing: today the Germans are the largest population group in Austria and will number 225,000 people in 2023.

The prevailing opinion was to equate Romanians with gypsies and to fuel old prejudices. Austria has always been famous for categorizing refugees into good and bad, today the good refugees from Ukraine and the bad ones from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq.

In fact, I know from friends, such as the artist Virgilius Moldovan, that he was stuck in a refugee camp for two years after his escape (October 1986) and that it took 3 years before he was able to bring his family to join him (in 1989, two months before the revolution). Hard, poorly paid work followed and it took years before the family was able to settle down. Today the whole family is established, one of his daughters is a doctor, they are all established in the Austrian Society and paying taxes.

My friend Gabriela Iszlery, from the Hungarian minority in Romania, fled with her family when she was still a child. They also ended up in a refugee camp. Later, her mother worked in a textile factory in Burgenland, where Romanian women workers provided cheap labour. She graduated from high school in Austria and was still required to take a language test for citizenship. Today she is working at MAK / Financial department.

These are just two examples of many, but they are good examples for full integration. Even though it is hard to live in Austria with a m migration background.

Today, around 47,000 people from Romania live in Austria, the majority of them in Vienna.

In 2021, a total of 107,100 Romanians were in employment: 63.3% of them were employed and 31.4% were self-employed. While 86.3% of men were employed, 45.8% of women were self-employed. On the other hand, the proportion of women (48.1%) who were self-employed was more than five times higher than that of men (9.4%).

From my point of view, they live in four different universes:

When I was at events organised by Romanian-Austrian society, I had the impression that only „old, wealthy“ people from Romania live in Austria, well-established, even assimilated.

A second group of rather young Romanians, on the other hand, live in working-class neighborhoods like Floridsdorf and often live in precarious situations.

The third group, by far the smallest, are Roma who run various businesses but do not always fit the cliché of beggars.

The fourth and very important group for Vienna are the artists from Romania. Thanks to their good theoretical and practical training, they have been shaping Vienna’s art scene for years.

From the 1980s onwards, the gallery scene in Vienna also showed great interest in Romanian artists.

It is an Austrian phenomenon that artists from other nations are discovered for their own purposes and established on the local art market. It’s a bit like a colonist approach. The interest is brief, the sustainability questionable.

After the revolution, more and more Romanian artists were exhibited. However, interest in the art scene is changing just as quickly as fashion. New streams of refugees have also awakened the art market’s interest in unknown scenes. The ulterior motive behind all these superficial interests is to make a quick buck at the expense of people who are at our mercy.

In the same way, the gold rush mood of the Austrian economy and banks in Romania, the neocolonial tendencies, faded away after the economic crisis of 2008. Some companies have remained and are still exploiting nature and people, as we could see in the case of the deforestation in the Carpathian, with the significant participation of a Viennese company.

A good example of the hypocrisy of the current Austrian government is its handling of the Schengen Agreement. Some time ago it was announced that border controls for flights from Romania had been cancelled. Because Austria needs carers from Romania to maintain its ailing care system for the elderly. None of the politicians thought about the fact that most carers do not come by plane, but in the cheap minibuses. The queues on the motorway before the Hungarian border are enormous. Once again, only the wealthy, businessmen and exploiters benefit from the renewal of the law.

History shows that Austria is a construction of many different peoples and their traditions, just like Romania. The minorities in both countries have shaped daily life, moulded the culture and given the countries a special character. We should celebrate this diversity together instead of fighting it.