Claudia Larcher

Baumeister (2012, 8:30 Min)

The Artist In The Machine (2022, 3:30 Min)

Self (2015, 7:30 Min)

Me, Myself And I (2022, 5:30 Min)

Claudia Larchers künstlerisches Interesse gilt einerseits Räumen, die mit Vertrautheit und Erinnerung verbunden sind und andererseits Körperbildern, die keiner Abbildrealität zuzuordnen sind. Dabei entstehen Videoanimationen, Fotomontagen,

Objekte und Collagen in denen einerseits topographische oder physiologische Gegebenheiten, andererseits Erinnerungs- und Vorstellungsbilder verarbeitet und verwoben werden.

Als Grundlage ihrer Videos dient meist eine Kombination aus Bewegtbildern und Fotografien, die zu oft unmöglichen Raumkonstellationen oder Physiognomien animiert werden.

Aktuell experimentiert Claudia Larcher mit Algorithmen und Künstlicher Intelligenz als Werkzeuge für ihre Animationen. (Gerald Weber)

BIO

Claudia Larcher* 1979, Austria

Born in Bregenz. Studied sculpture, multimedia and intermedia art at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna. Since 2005 participation in exhibitions in Austria and abroad in the fields of video animation, installation and LiveVideoPerformance.

About the films:

Baumeister (2012, 8:30 Min)

The camera moves in a spiral motion along the ceiling, picking up its circular shape by tracing the joint between two ceiling elements; rectangular lamps emerge one after the other like the schematic representation of sunbeams or the spokes of a wheel; in parallel, the sound conveys an atmospheric, reverberating „dripping“ – at least that is one of an infinite number of possible associations.The video Baumeister describes the deserted interior of the ORF studio in Dornbirn. Planned and executed by Gustav Peichl in 1969-1972, its formal basis is the spiral – that figure which results from a line unfolding from the inside to the outside, and which is also found on the human body: at the navel or in the ear….

In a similar way that architecture translates the function of hearing, Claudia Larcher’s video refers to seeing. The camera is the eye that tries to grasp the structure of space by tracing, repeating its movements. But seeing (just like hearing or feeling) is not an objectifying act. It is closely linked to the memories of the one who perceives. In this respect it never produces a continuous space of experience. Rather, it produces images consisting of superimpositions, transformations, condensations. (Ines Gebetsroither)

The Artist In The Machine (2022, 3:30 Min)

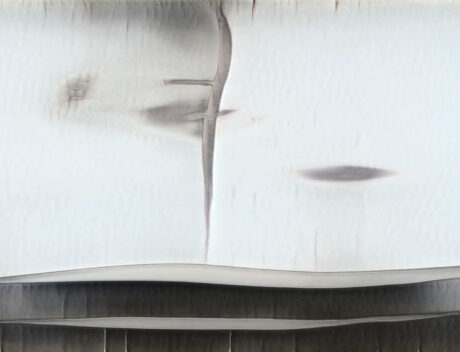

Form, it is sometimes said, is like a mechanical framework that is only brought to life with corresponding content. Architectural form can also have an inherent rigidity – as long as it is not “animated” through artistic means or practical everyday solutions. But what if this animating function itself is outsourced to the machine? What if the artistic process is delegated to computational procedures? Is this less creative than a result conceived by humans, or is there possibly “more” of the creative evident here?

Claudia Larcher investigates this complex of questions by means of an experimental arrangement she has designed. She fed the data from her collage series Baumeister (2011–2021) into a self-learning neural network – or rather two of them, consisting of a “generator” and a “discriminator” (together called “GAN”). The program called “Artificial Assistant No. 2” is intended to create works based on this setup – and does so brilliantly! At first one seems to perceive a solid structure emerging, in the form of a greyish modernist façade. But such old-fashioned illusions soon come to an end. The crafty machine-mind constantly stretches, distorts, and bends the image, which simply will not come to a stop. Even in the second attempt, nothing here really wants to become a “form” – or if it does, then it’s something that lies beyond all formalistic thinking. Adding to all this is the soundtrack, which is synchronized with the unstable wafting image, and derived from it using “assistants” called Dynascore and Imaginary Soundscape. It hammers and whistles, trumpets and whirrs – while the digital master builder at work here condenses its work into ever more amorphous streams of the Art Informel.

In the end, this android didn’t dream of electric sheep, but instead freed itself from any “humanoid” appearance. (Christian Höller)

Translation: John Wojtowicz

Self (2015, 7:30 Min)

The skin is the body´s largest sense organ: delicate and at the same time extremely robust, it has to fulfill various functions, from excretion through to storage of nutrients. Although one hopes to shed it at a metaphorical level, it simultaneously serves as the bearer of our identity, which can be written on, marked, and changed. It is more than simply a shell, more than a border between inside and outside, it is the self, (not only) in Larcher´s video.

A laconic-analytical camera pan shows a close-up of it at the beginning: pores, fine hairs, a mesh of blue veins that shine through the delicate membrane. In what follows, details yield a whole, and one seems to recognize neck, armpit, and upper arm. Suggested here is an interior that this skin stretches around. But suddenly there are „wrong“ extensions, „impossible“ elongations and overlaps. The border between inside and outside is successively dissolved and flows into a „liquefaction“ of the image in whose blurriness, pink masses multiply and caverns protrude until the camera returns to the start again.

The complex and dramatic sound (by Constantin Popp, once again) carries the originally mentioned references and transfers the images into a tale of a fragile self; „skin horror“ and genetic mutation phantasm. Something cracks here, air is drawn in, the whirring and rustling intensify, scraps of conversation push through. As more traces of reality become audible, it becomes increasingly uncanny. This organ, which surrounds us everyday, has become independent, obeys its own, uncontrolled dynamics, whose calm at the end will only be temporary. (Claudia Slanar)

Me, Myself And I (2022, 5:30 Min)

The triplet in the title basically give it away already: identity in the digital age, especially in the face of image production and reproduction processes, is subject to incessant multiplication. Or to put it another way: the ego, what one could also call the “digital subject”, is now subject to a technologically fuelled tendency to splinter, while also being shrouded in a nebulous illusion of unity.

Claudia Larcher’s „Me, myself and I“ does nothing less than cause this moment of fragmentation and simultaneous resynthesis to collide productively. The experimental arrangement is as simple as it is captivating: Larcher has added 350 photographs of herself (up to the age of 24) to a GAN (Generative Adversarial Network) which then spits forth a continuously deforming flow of images containing perspectives on identity that go beyond the original photographs. Babyface, girl’s head, young woman, fast forward into old age and back again to the infantile – all this in an incessantly morphing stream, allowing one to dissolve imperceptibly into the next. This results in the staging of a digitally mediated becoming, seen in equal parts as productive disappearance as well as constant re-creation – the elimination of all that has gone before up to the point of complete abstraction, with simultaneous reconstitution and anticipation of what is yet to come. Grotesque deformation meets malformed refocusing, an organic-synthetic hybrid, in which a laughable series of comical faces flashes repeatedly, like what we know from Snapchat and other image processing filters.

The soundtrack proves that all of this is not based on any kind of master narrative about what AI can do or possibly wants. Here, Larcher has processed dialogues that she has conducted with various chatbots on the subject of identity and turned them into a script that interconnects fragments of ego perception in a multidirectional manner. The „reflexive self-reference“, which is repeatedly addressed as the core of every identity, may itself be nothing more than a placeholder for a multiplicity that cannot be contained. Or for the edge of a non-existence, which is expressed just as beguilingly in the cheerfully delirious fragments of portraits. (Christian Höller)